In June, 2011 Standard and Poor’s warned plans for the private sector to roll over Greek debt could trigger a default under its ratings criteria.

Standard and Poor’s also said that, depending on the circumstances, it viewed “certain types of debt exchanges and similar restructurings as equivalent to a payment default”. In their view, “any such transactions would likely be on terms less favourable than the debt being refinanced, which we, in turn, would view as a de facto default according to Standard & Poor’s published criteria,” the agency said.

Fast forward to March 9th, 2011. Today, Greece took an important step towards its second bailout after it managed to win a crucial debt swap. The Greek deal with its lenders is the largest restructuring of government debt in history. Under the deal, banks and other financial institutions have agreed to exchange their existing Greek government debt for new bonds – now worth much less and paying a lower rate of interest.

According to the Greek government website, the deal involves 172 billion euros worth of debt under exchange with some investors taking a loss of up to 74 percent. At a press conference in Athens, Greek Finance Minister Evangelos Venizelos welcomed the deal saying, “We can say now that instead of what usually occurred, we are today reducing the debt.” Based on Standard and Poor’s assessment from last year, does that mean that Greece just defaulted? The short answer is yes – under the previously assigned status of “Selective Default”.

In a February 28th interview with Bloomberg, head of sovereign ratings at Standard & Poor’s, Moritz Kraemer, discusses Greece’s “Selective Default” status and European sovereign debt.

But what’s really going on here? On March 2nd, European leaders signed a German-driven fiscal compact treaty to enforce EU deficit-cutting and debt reduction rules more strictly. Key states such as Italy and Spain are implementing tough spending cuts and pension and labour reforms; and now, more European countries may be forced to adopt austerity measures – not just Greece.

Rewind to 1932 and the Great Depression. Didn’t we learn that tax increases and cut-backs do not promote economic recovery during a contraction? Last month it was reported that Greece’s economy shrank, on an annualized basis, 7.0 percent in the fourth quarter of 2011. While on March 8th, Greek statistics service ELSTAT said the overall jobless rate rose to 21.0 percent and that, for the first time on record, more than half of Greek youth (ages 15-24) are unemployed. The overall unemployment rate at the height of the Great Depression in the United States was 24.9 percent in 1933.

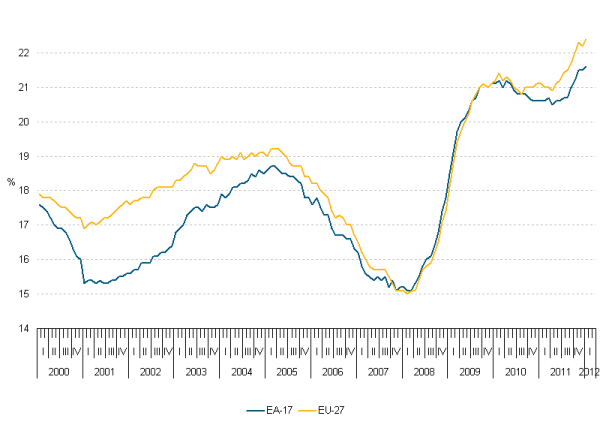

But this is not just a Greek problem. Unemployment rates in the EU are very high. Currently, the youth unemployment rate for the EU-27 and EU-17 is hovering around 22%. In Spain, the fourth biggest economy in the eurozone, official unemployment is more than 21 percent while youth unemployment is over 49 percent. In comparison, the unemployment rate in the United States is 8.3 percent and youth unemployment is in the neighbourhood of 18 percent.

The problems facing other European countries – Portugal, Ireland, Italy and Spain – have until now been peripheral to those of once mighty Greece. But with the recently signed fiscal compact treaty, the working-class in the heavily indebted peripheral countries are bracing for what’s coming next.

For an excellent overview on European debt visit the European Commission eurostat website – CLICK HERE.

Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter Become our facebook fan

Become our facebook fan

Comments are closed.